20

2013Art and Emotion

Art has a transcending ability to connect and communicate with people. It forms a unique relationship between the artwork and the viewer, sometimes very articulated and other times strangely enigmatic.

If we want to fully understand a particular work of art, we must take into account several pieces of information – who created it? What are its intentions? What do we know about the artist’s life, background and previous work? Equally valuable is the knowledge of the artwork’s content and context because all art is made in a specific time and place, surrounded by a particular political and social setting. This accumulation of knowledge accompanied with our initial gut reactions and later responses alter the process from ‘viewing’ the art, to ‘experiencing’ the art. I want to focus on this emotional connection that is created when we attempt to appreciate art or associate it with our own life experiences. What are the possibilities of art? Can it tap into the emotions that make us human?

One does not paint for design students or historians but for human beings, and the reaction in human terms is the only thing that is really satisfactory to the artist

– Mark Rothko (Seitz, W.C 1983)

I believe creating art is a natural human behaviour. As children, we instinctively use art to communicate, not specifically to others, but as a way of conveying and expressing our feelings. It is our primary language before we even learn how to speak properly. Through art, we are granted a freedom to portray emotion in a much more creative manner than any other form of language or communication. It is a language all cultures can understand, interpret and relate – Art is universal.

Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once we grow up

– Pablo Picasso

‘Guernica’ (1937) – a childlike painting by Picasso which shows the tragedies of war and the suffering it inflicts upon individuals, particularly innocent civilians.

Picasso (1881-1973) said it took him four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child. He understood the importance of maintaining the innocence and freedom that we all had as children – the ability to paint something that could not be articulated with words; to produce a painting which embodies something that only it can. Prehistoric cave paintings were produced for the same purpose, as a way of communicating with others. This proves that we have a natural artistic capability and necessity to communicate with one another. I really want to delve deeper into why this is, which will help explain why art and emotion are very closely related.

Art is the Queen of all sciences communicating knowledge to all the generations of the world

– Leonardo Da Vinci

The left-brain, right-brain dominance theory states that the right side of the brain is best at expressive and creative tasks. Some of the abilities that are popularly associated with the right side of the brain include expressing emotions, reading emotions, colour, images and creativity, all of which are fundamental aspects of art. Whether or not we are left-brain or right-brain dominant, we have a natural biological connection to associations with art. We all have a creative side and it is this that creates a need and appreciation for art, whether we are making it, or viewing it. Rothko believed that there was a wealth of art in one’s subconscious and he relied on that part of the brain for help with his painting.

The world seems to me witnessed an evolution of artistic expression and its purpose – we have realised that the emotional responses we generate, are the key to experiencing the pinnacle of art. Art is continually changing because artists develop ideas, concepts and themes through the influence of their global and personal world and other artists and art movements. The 20th century was a major turning point in our conceptions of art. The artist no longer felt the need to reflect reality, but rather tries to convey expression and emotion through form and colour, in a bid to break with tradition and reject classical notions of what is beautiful in art. All of these factors helped give birth to abstract art and later, abstract expressionism.

‘Autumn Rhythm’ (1950) – Jackson Pollock (1912-56) was at the height of his powers when he produced this “drip” painting, which is a powerful example of abstract expressionism and ‘action painting’.

Abstract expressionism was an American post-World War II art movement. The disaster and consequences of the war changed the outlook of a society that became troubled by the immoral and irrational side of humanity. An emergence of young artists, to be later known as abstract expressionists, sought ways to express their concerns in a new art form full of meaning, substance and emotion.

At a certain moment the canvas began to appear to one American painter after another as an arena in which to act. What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event

– Harold Rosenberg (Art News 1952)

Previous movements such as Surrealism, with its emotional intensity and emphasis on spontaneous and subconscious creation, and artists like Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), the pioneer of abstract art, were very influential both conceptually and aesthetically. Even though many aspects of abstract expressionism utilised natural and involuntary actions, the majority of the most successful paintings demanded careful planning.

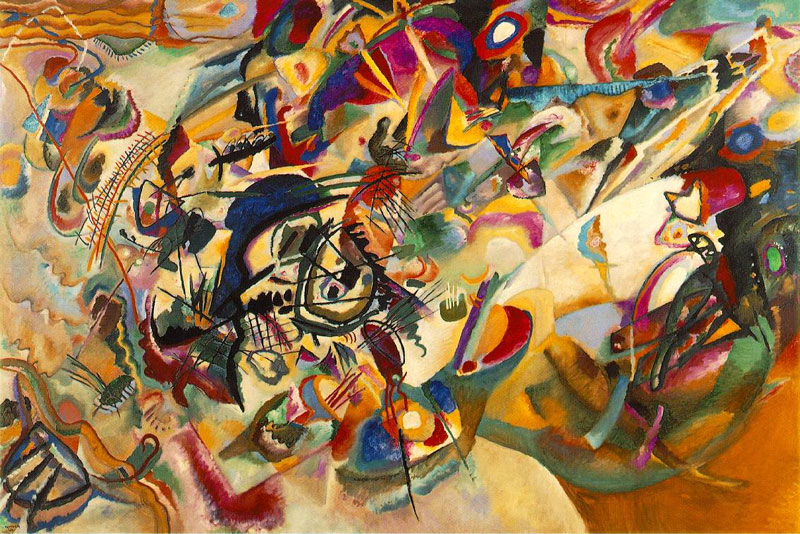

‘Composition VII’ (1913) – Wassily Kandinsky painted a compositional hurricane of swirling masses of colour and form. It “combines the themes of The Resurrection, The Last Judgement, The Deluge and The Garden of Love in an operatic outburst of pure painting”.

Kandinsky felt that painting was similar to composing music, by creating a composition to trigger certain emotions, feelings and memories. He strongly believed in the similarities between colour and music so much so that the viewer might hear the colours and see the sounds. A common theme in his first seven compositions was the apocalypse. These paintings evoked a utopian idea of what the apocalypse could bring because he believed the world had lost a lot of faith, belief and spirituality, and this was his orchestration of restoring what was lost. He wanted his large compositions to immerse and overwhelm the viewer with what the painting is saying. Jackson Pollock also sought to engage the viewer with his subconscious creations.

Jackson Pollock expanded and developed the abstract expressionism with his revolutionary approach to painting. He believed that the process of making art was an emotional experience just as important as the finished work itself. Harold Rosenberg, an art critic who coined the term ‘action painting’ in 1952, shared the same principles as Pollock in that the importance had moved from the object to the practice, with the completed painting merely a physical remainder left by the creation of the painting, which was in fact the real work of art. When you view his work we are taken on a journey, through his drips of paint, where you reveal the world of his subconscious mind – his life, his beliefs, his emotions, his feelings, his struggles. You begin to follow the rhythm and choreography of his actions: the varying thickness of the paint which builds up the multiple layers of work, the physical presence when he violently throws paint at the canvas, the emotional essence of the oils gently dripping onto the painting. He rarely leads your eye off the canvas, he had an ability to contain the viewer’s gaze in the painting which would prolong and enhance the experience. Pollock had clear intentions to create an emotional relationship between the viewer and the painting; it is this unique connection which nourishes the senses.

Some abstract expressionists began painting with a highly articulated and psychological use of colour covering large areas or ‘fields’ of the canvas, from which Clement Greenberg coined the term ‘colour field’. Artists like Mark Rothko (1903-70) and Barnett Newman (1905-70) produced paintings on a monumental scale which were intended to overwhelm the viewer and pull them into an unknown space against their will.

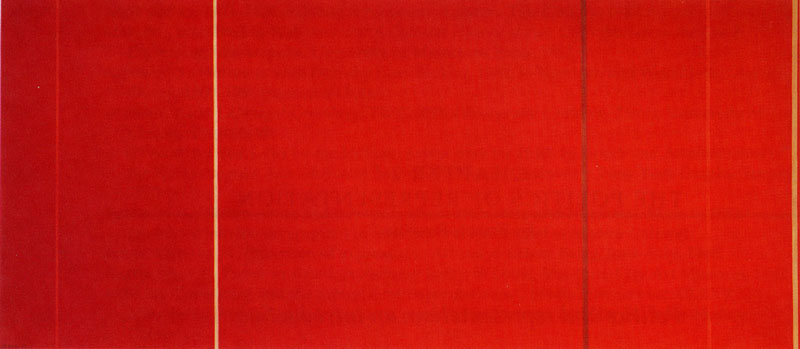

‘Vir Heroicus Sublimis’ (1950-51) – Barnett Newman’s painting which means “man, heroic and sublime” encourages viewers to react to the colour according to their instincts, completely separated from its societal connotations.

In colour field painting, “colour is freed from objective context and becomes the subject in itself”. The viewer succumbs to the deeply expressive and sensual qualities of the performing colours. Like Rothko, Newman felt that “There is a tendency to look at large pictures from a distance. The large pictures in this exhibition are intended to be seen from a short distance”, although, he rejected the expressive brush strokes and ragged edges of the colour fields practiced by Rothko, something which I found enhanced the experience during the creation of his art and left a more subconscious, natural residue on the painting.

…I want to be very intimate and human. To paint a small picture is to place yourself outside your experience, to look upon an experience as a stereopticon view or with reduced glass. However you paint the larger picture, you are in it. It isn’t something you command!

– Mark Rothko (Clifford Ross 1951)

Rothko was one of the foremost of the colour field painters, and is seen as a leading figure in abstract expressionism, even though he rejected being categorised as an abstract expressionist, and even denied being an “abstract painter”.

For me, Mark Rothko stands as the perfect example of what I believe to be true, which is, going back to my earlier point, that art is a natural human behaviour and a form of conveying our emotions, which is evident in the prehistoric cave paintings thousands of years ago and can be seen with children in our modern society. Rothko wrote about the similarities he saw in the art of children and the work of modern painters, who were strongly influenced by primitive art, saying “often child art transforms itself into primitivism, which is only the child producing a mimicry of himself”. It took him over 20 years of practicing as an artist to realise that the best way of achieving this spontaneous nature of art was through the use of colour. His large sheets of colour were the performers in his paintings, controlling our senses and emotions.

For Rothko, colour is “merely an instrument”. The “multiforms” and the signature paintings are, in essence, the same expression of “basic human emotions”.

– (Wikipedia: Mark Rothko 2012)

Rothko’s described his “multiforms” as large bodies of human expressions, having their own presence – living and breathing. The contrasting panels of colour had a movement all of their own, sometimes they appeared to detach from the canvas like a hovering cloud, overwhelming the viewer and making them feel “enveloped within” the painting. He never wanted these masterpieces to appear as a thing of beauty, he was more concerned with overpowering people, taking them into an unknown space where they would “recover their humanity”.

‘Black on Maroon’ (1959) – The painting comes from one of three series painted by Rothko 1958-59.

The painting was part of an intended commission for the Four Seasons restaurant where he wanted to bring in a feeling of human tragedy. He wanted to evoke the emotional force of the old masters, “After I had been at work for some time I realised that I was much influenced subconsciously by Michelangelo’s walls in the staircase room of the Medicean Library in Florence. He achieved just the kind of feeling I’m after…” Michelangelo’s paintings, combined with other architectural effects, had created an oppressive atmosphere in the room. Rothko felt so bitterly towards the people who ate in the restaurant that he wanted his walls to shock them, to trap them in a room where they felt they couldn’t escape. He envisaged these large murals a wordless teaching, an antidote to the triviality of modern life.

I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions – tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on – and the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures show that I communicate these basic human emotions. …The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.

– Mark Rothko ( Selden Rodman 1957)

Rothko wanted to have complete control over the viewer, so much so that he made sure his paintings were positioned correctly on the wall and received the perfecting lighting, while also advising the viewer to stand as close as 18 inches away from the canvas. He felt all these factors were vital in order to create an intimate, personal connection with the viewer which, in turn, would allow the paintings to project their full power.

While looking through his masterful collection of “multiforms”, in a way, you feel that they have become his visual biography. We begin with vibrant reds, oranges and yellows, expressing feelings of energy and ecstasy, and finish with dark browns, blues and greens, which I think represented the growing darkness in his personal life. His paintings represented the feelings he had towards the world at that time. Sometimes his pictures were emotionally stimulating and sensually addictive and other times they consumed our minds with a damning feeling of fate and death. His fields of colour were more like windows of colours, acting as gateways into our subconscious, where we saw our past and our future, our entrances and our exits, our beginnings and our endings, and everything between. I believe that he was simply sharing his emotions aesthetically through art, just like our prehistoric ancestors did and children do today.

By deciphering this complex relationship, which suggests art and emotion coincide with one another, I’ve realised that it is not just about the aesthetic experience, which is fuelled by pleasure or displeasure, it is more about our emotional responses, the sensual reactions that we may have no control over. Artists like Picasso, Kandinsky, Pollock and Rothko can personify this experience. It doesn’t matter if the work is representational or not, what matters is the sense of intimacy and emotion directed from the artist, through the art, to the viewer. When the artist achieves this, we experience an uncontrollable burst of emotion, which can trigger certain feelings and memories of our personal lives and of the world we live in. These associations are intimate, distinctive and irreplaceable. It is there in that moment, where we feel the power that art can possess, and when we realise art’s true purpose in life.

Rose Art

Enjoyed your perspectives Conor. That “connection” you speak of between the viewer and the piece can be very powerful indeed.

Sharon Cummings

Very well done…insightful and thorough blog!

Meghan Deinhard Also FireBonnet

I absolutely agree with Sharon. I particularly relate to the Picasso quote about remaining an artist when we grow up. Thank you for leading me to your blog through FAA.

Glen Smith

Certainly the expression of emotions is a very important element of art but it limits its possibility. Many great works do just this. Your post is all true as far as it goes. However, it is more about you placing a limit on your idea of what “art” is as a definition than what is important in the overall creative function of man. What do you do with John Ruskin, icons, etc? The value of “art” is not limited to processes of personal feeling but can certainly include

perception of cause and effect, behavior modification, thought- as well as feeling.

A person may keep the beauty of being a child but there is also the possibility of more.

All is open to art.